Late last year, Stephen Woroniecki and I (Niki) posed a provocative question:

What would it mean to act as if we are already living in the world we hope to create?

Some of the responses we got were sceptical –That is denial! We have to face the truth about what we are doing wrong before we can look to solutions! Fair enough, there is a kind of complacent hope that leads to inaction. Some see ‘climate delay’ as a form of complacent hope that functions as the new climate denial. She’ll be right mate, as we say in New Zealand. The rapidly growing Extinction Rebellion and the School Strike movement have called out such complacency in the face of the doom they see impending from every direction.

But we also received another kind of response; thoughts about what it might mean to step into a space of trust and hope that, just sometimes, side lines the problems and instead acts in the spirit of prefiguration: leaping ahead of the game and thereby helping to change it.

In this blog we outline four possibilities of such thinking that we have crafted from the ideas we received and our own thoughts. These are a kind of edgework that sees cracks in current modes of practice and tries to prise them open. We see the possibilities below as aligned with a renewed interest in speculative fiction and the promise of artistic and performative methods for reimagining sustainability. We’d love to hear your reactions.

1. Assume that those you encounter want a world that promotes wellbeing for all.

Much of our current political discourse inherits a dedication to polemic and polarisation. There is no shortage of commentators decrying attempts at bipartisan solutions as ineffective, slow, or centrist (as if that were a dirty word). In its determination to keep alive old paradigms and caricatures of the ‘right’ and the ‘left’; such discourse prevents us from rising above the game, even for a second, to see its effects and how we contribute to its dysfunctions. I (Niki) subscribed to the Guardian Weekly for six months, but in the end grew tired of the plethora of articles that demonised Trump. Such articles can be riveting to read and create a sordid sense of self-righteous solidarity with other Trump-bashers, but they can seduce us into thinking ‘they’ are all bad, and ‘we’ are all good.

What if, instead, we were to imagine that beneath the hotly contested debates were people trying to develop sustainability solutions? That Trump or the local equivalent that we love-to-hate was doing what they felt was best? That people we label as ‘sexist’ or ‘racist’ have a contribution to make and perhaps they talk as they do because they are locked in the same us/them game that we are? An immediate effect of thinking in this way is to assume that everyone has a role to play in solutions and can be brought into the game. We are not the only people with a monopoly on visions for the good life, and what’s more there will always be politics – people who slow the pace of change, those who want to speed things up, and those who want to go fast in what (we think) is the wrong direction.

In a small way I (Niki) tried to do this in my former role as the leader of a sustainability network at my university. I talked as if sustainability is a problem we are all trying to solve and so, I think, our network has avoided creating a sense that we have friends and enemies. Yes, some of us are more central to making change in this domain, but we do not see our task as constructing and then beating opponents – instead we are trying to realign the finite games we are all caught in.

It is hard to take sides on an issue that isn’t framed as a debate. And when everyone is on the same side, conversations rather than boxing matches, become possible.

2. Act as a guardian to your land, among other guardians.

What if, instead of striving to be the next hero of the hour, we were to uncover and highlight existing place-based commitments to restorative work that cast a legacy of collective worth?

Many – probably all – cultures have concepts that encourage people to be guardians or stewards of the natural environment. For Māori in Aotearoa/New Zealand, one such concept is kaitiakitanga. As described by Daniel Hikuroa, kaitiakitanga is a complex system of knowledge and practices that result in careful observation and care for the mauri, or life force, of natural entities – be they mountains, forests, rivers, animals or the ocean. Such entities are assumed to have intrinsic value and talked of as ancestors to the people of that land.

Even within Western models – which are often described as exploitative and soulless – we have a strong ethic of conservation. There are 29 national parks in Sweden and in New Zealand 32% of the land is within protected areas. The Antarctic Treaty system is a comprehensive international agreement that acknowledges the inherent value of Antarctica and our need to protect it. We could go on: for each example of how we are destroying the planet is another example of how we are attempting, often successfully, to preserve or restore it.

Often such guardianship emerges out of long histories of interrelationship, contemplative action and ingrained wisdom which develops connections between a place and its people. These are deep relationships that by necessity are also slow moving. Rather than being interactions capable of instantaneous accounting, like Facebook friends or LinkedIn connections, place-making and place-shaping happens on timescales that may dwarf the lifespan of any particular individual.

When we talk as if we alone are fighting the tide of Western destruction and we alone are facing catastrophic threat to our natural environment, we ignore our history as guardians. When we position ourselves as keepers of a single bright idea or game-changing sustainability solution, we centre ourselves – casting a long shadow egocentrism into the future, rather than committing to a collective. This may blind us to the wisdom of those who – often quietly – get on with doing what needs to be done to nurture life. We too can act as guardians of the ecosystems and communities that are our home, rather than feel we must solve it all, right now, or we are done for. Nurturing guardianship in ourselves and others might, in the end, be more effective than scrambling for the Big Solution to the Big Problem.

3. Act as if we have time.

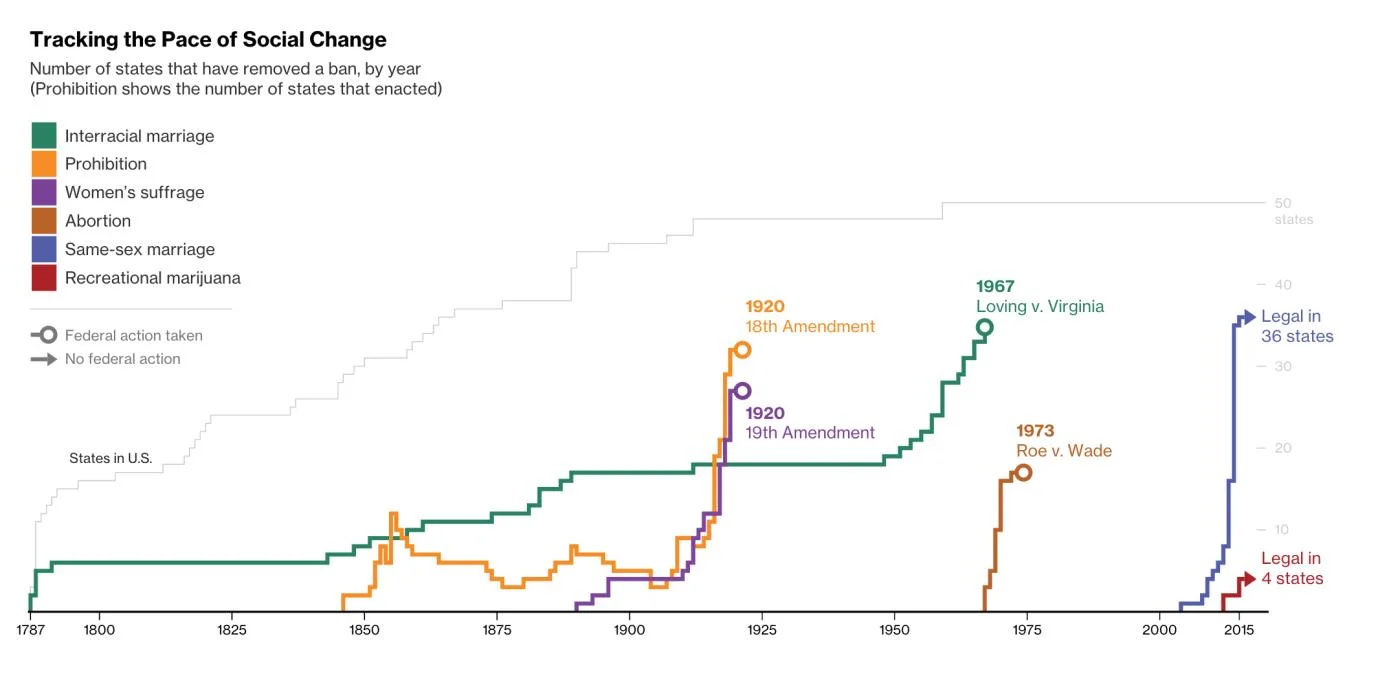

A recent framing of climate change declares that we have 12 years left to bring about major changes to our entire global system or we are doomed. As Niki has previously discussed, such rhetoric has two problematic components: it ignites a combination of fear and shame that often makes us withdraw, and it gives most people who encounter it no viable way to act on the information provided. The temptation is to argue over whether or not the information cited is correct, polarising readers into those who buy its message and those who don’t. As argued in an opinion piece in the Washington Post, Michael E. Mann, Susan Joy Hassol and Tom Toles, such frenzied rhetoric may prevent us from moving forward with ‘confidence’.

But what if we had time? If we had time, we might listen to each other more carefully and construct arguments and plans that pull together our various perspectives. We might care for the other – their knowledge, their experience and their right to dissent. As in a recent blog by Stephen, we might live with, and in, the diversity that characterises real human experience and exchange, and not just heed the mathematics of climate data.

We might too, feel what is happening around us and gain a better sense of what we want to preserve and what we want to give up in the reshaping of society. Remember that emergency action is rarely radical. It attempts to solve an immediate problem rather than to set up new systems that will be viable into the future.

The recent Brexit debate has shown the malfunctioning of leaders who do not take the time to get grassroots support for their top-down policy changes. In relation to climate, the Gilet Jaunes movement was triggered by a too-quick, top-down intervention in fuel prices. For all the talk of transformative action like the Green New Deal, and even the consensus emerging that climate change must be countered by structural change, there is precious little attention given to representation. Extinction Rebellion is calling for Citizen’s Assemblies that might help to build the legitimacy for such far-reaching transitions.

If then, we acted as if we had time to respond to the major issues we face, we might have far reaching conversations about the society we want to live in. Imagine the power we would hand to the politicians who care deeply about these issues if we were able to say to them: ‘I’ve worked alongside those in my school, business, organisation and community and this is what we care about.’ Conversations such as these take time and patience – which we would have if we weren’t always pushing to get change right this minute.

4. As best you can practice the future you imagine.

What if sustainability was not a promised land but a journey into unknown territory?

Sustainability is not a state it is a process. We will both never be sustainable and already are sustainable – depending on how you look at it. There may have been a time in human history when we were so well adapted to our natural environment that we could act without awareness of the consequences of our actions. But that horse has bolted. Instead, there will always be issues, and there will always be people in various stages of response to those issues. We can talk about ‘denial’, ‘the attitude-behaviour gap’, ‘addiction to oil’ and the various other frailties of our species, or we can recognise ourselves as beings that have created a world in which we do not, and never will, quite fit. Our task, from this perspective, is to try and act a little more consistently with reality (as we understand it) and avoid practices we consider harmful. This isn’t just about so-called personal actions – like riding a bike or avoiding plastic bags – it is also about political actions – like contributing to movements for the common good. Action for a better world isn’t the act of people in an unsustainable world, it is the act of people trying to create a sustainable world: which is as sustainable as we will ever be.

___________________

In writing this, we are not trying to claim there are no problems or that these problems will simply fade away if we are all positive. But we are trying to claim that endorsing rhetoric which frames us as on the brink of environmental catastrophe is not the only way to ‘man up’ and face ‘the truth’. We can also get on with it by treating sustainability as a game with no end and in which trust and hope are a vital part of the play.

See here for Stephen Woroniecki’s blog.

Click here to receive blog posts via email.